|

|

| (26 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| {{Other uses}} | | {{Infobox Nonliterary Works |

| {{Good article}} | | | image = |

| {{IndicText}} | | | image_size = |

| [[File:Lord Mahavir Gold.jpg|thumb|right|[[Mahavira]], The Torch-bearer of Ahimsa]]

| | | alt = |

| | | | caption = <!-- titled displayed below that image --> |

| '''Ahimsa''' ({{lang-sa|[[अहिंसा]]}}; [[IAST]]: {{IAST|ahiṃsā}}, [[Pali|Pāli]]:<ref name="Johansson2012">{{cite book|author=Rune E. A. Johansson|title=Pali Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader and Grammar|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=CXBmlQvw7PwC&pg=PT143|accessdate=8 August 2013|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-11106-8|page=143}}</ref> {{IAST|avihiṃsā}}) is a term meaning do not injure. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root ''hiṃs'' – to strike; ''hiṃsā'' is injury or harm, ''a-hiṃsā'' is the opposite of this, i.e. cause no injury, do no harm.<ref>Mayton, D. M., & Burrows, C. A. (2012), ''Psychology of Nonviolence'', The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, Vol. 1, pages 713-716 and 720-723, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9644-4</ref><ref>[Encyclopedia Britannica], see Ahimsa</ref> Ahimsa is also referred to as nonviolence, and it applies to all living beings including animals.<ref name=historyindia2011>Bajpai, Shiva (2011). ''[http://www.himalayanacademy.com/media/books/the-history-of-hindu-india/the-history-of-hindu-india.pdf The History of India - From Ancient to Modern Times]'', Himalayan Academy Publications (Hawaii, USA), ISBN 978-1-934145-38-8; see pages 8, 98</ref> | | | abbreviation = |

| | | | short_description = |

| Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues<ref name=evpc/> and an important tenet of major [[Indian religions]] ([[Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], and [[Jainism]]). Ahimsa is a multidimensional concept,<ref name=arapura/> inspired by the premise that all living beings have the spark of the divine spiritual energy, to hurt another being is to hurt oneself. Ahimsa has also been related to the notion that any violence has [[Karma|karmic]] consequences. While ancient scholars of Hinduism pioneered and over time perfected the principles of Ahimsa, the concept reached an extraordinary status in the ethical philosophy of Jainism.<ref name=evpc>Stephen H. Phillips & other authors (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (Second Edition), ISBN 978-0123739858, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701-849, 1867</ref><ref name=chapple1990>Chapple, C. (1990). Nonviolence to animals, earth and self in Asian Traditions (see Chapter 1). State University of New York Press (1993)</ref> Indian leader [[Mahatma Gandhi]] strongly believed in the principle of ''ahimsa''.<ref>Gandhi, M. (2002). The essential Gandhi: an anthology of his writings on his life, work, and ideas. Random House Digital, Inc.</ref> | | | alternative_names = |

| | | | in_other_languages = Non-violence {{grey|(English)}}<br/>अहिंसा {{grey|(Sanskrit)}} |

| Ahimsa's precept of 'cause no injury' includes one's deeds, words, and thoughts.<ref>Kirkwood, W. G. (1989). Truthfulness as a standard for speech in ancient India. Southern Communication Journal, 54(3), 213-234.</ref><ref name=kaneda2008/> Classical literature of Hinduism such as Mahabharata and Ramayana, as well as modern scholars<ref>Struckmeyer, F. R. (1971). The" Just War" and the Right of Self-defense. Ethics, 82(1), 48-55.</ref> debate principles of Ahimsa when one is faced with war and situations requiring self-defense. The historic literature from India and modern discussions have contributed to [[Just war theory|theories of Just War]], and theories of appropriate [[self-defense]].<ref name=balkaran2012>Balkaran, R., & Dorn, A. W. (2012). [http://www.sareligionuoft.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/JAAR-Article-Violence-in-the-Valmiki-Ramayana-Just-War-Criteria-in-an-Ancient-Indian-Epic-.pdf Violence in the Vālmı̄ki Rāmāyaṇa: Just War Criteria in an Ancient Indian Epic], Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 80(3), 659-690.</ref>

| | | motto = |

| | | logo = |

| | | country = |

| | | language = |

| | | website = |

| | }} |

| | '''Ahimsa''' ({{lang-sa|अहिंसा}}; [[Roman Sanskrit transliteration|Roman Saḿskrta]]: ahiḿsá; [[:wikipedia:IAST|IAST]]: {{IAST|ahiṃsā}}, [[:wikipedia:Pali|Pali]]:<ref name="Johansson2012">{{cite book|author=Rune E. A. Johansson|title=Pali Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader and Grammar|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=CXBmlQvw7PwC&pg=PT143|accessdate=8 August 2013|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-11106-8|page=143}}</ref> avihiḿsá) is a term meaning benignity, non-injury. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root ''hiḿs'' – to strike. ''Hiḿsá'' is injury or harm. ''A-hiḿsá'' is the opposite.<ref>Mayton, D. M., & Burrows, C. A. (2012), ''Psychology of Nonviolence'', The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, Vol. 1, pages 713-716 and 720-723, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9644-4</ref><ref>Encyclopedia Britannica, see Ahimsa</ref> |

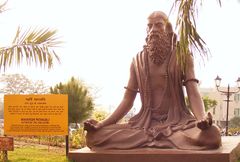

| | [[File:Patanjali Statue.jpg|thumb|240px|Statue of Patanjali at Patanjali Yog Peeth, Haridwar]] |

| | Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues<ref name=evpc>Stephen H. Phillips & other authors (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (Second Edition), ISBN 978-0123739858, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701-849, 1867</ref>, the first of ten principles in the ancient tantric/yogic system of morality, ''Yama-Niyama''. As such, it is also an important tenet of major [[:wikipedia:Indian religions|Indian religions]] ([[:wikipedia:Buddhism|Buddhism]], [[:wikipedia:Hinduism|Hinduism]], and [[:wikipedia:Jainism|Jainism]]). Over the years, Ahimsa has been interpreted in many different ways. In his book, [[A Guide to Human Conduct]], Sarkar analyzes the concept of Ahimsa and some popular interpretations of the term.<ref name=GTHC>{{cite book|last=Anandamurti|first=Shrii Shrii|title=A Guide to Human Conduct|year=2004|ISBN= 9788172521035}}</ref> |

|

| |

|

| ==Etymology== | | ==Etymology== |

| The word ''Ahimsa'' - sometimes spelled as ''Ahinsa''<ref name="Sanskrit dictionary">[http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/cgi-bin/monier/serveimg.pl?file=/scans/MWScan/MWScanjpg/mw0125-ahalyA.jpg Sanskrit dictionary reference]</ref><ref>Standing, E. M. (1924). THE SUPER‐VEGETARIANS. New Blackfriars, 5(50), pages 103-108</ref> - is derived from the Sanskrit root ''hiṃs'' – to strike; ''hiṃsā'' is injury or harm, ''a-hiṃsā'' is the opposite of this, i.e. ''non harming'' or ''[[nonviolence]]''.<ref name="Sanskrit dictionary"/><ref name="Shukavak N. Dasa">[http://www.sanskrit.org/www/Hindu%20Primer/nonharming_ahimsa.html A Hindu Primer], by [http://www.sanskrit.org/www/shukavak.htm Shukavak N. Dasa]</ref> | | The word ''Ahimsa'' - sometimes spelled as ''Ahinsa''<ref name="Sanskrit dictionary">[http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/cgi-bin/monier/serveimg.pl?file=/scans/MWScan/MWScanjpg/mw0125-ahalyA.jpg Sanskrit dictionary reference]</ref><ref>Standing, E. M. (1924). THE SUPER‐VEGETARIANS. New Blackfriars, 5(50), pages 103-108</ref> - is derived from the Sanskrit root ''hiṃs'' – to strike; ''hiṃsā'' (or ''hiḿsá'' in Sarkar's [[Roman Sanskrit transliteration|Roman Sanskrit]]) is injury or harm, ''a-hiṃsā'' is the opposite of this, that is benignity or non-jury.<ref name="Sanskrit dictionary"/><ref name="Shukavak N. Dasa">[http://www.sanskrit.org/www/Hindu%20Primer/nonharming_ahimsa.html A Hindu Primer], by [http://www.sanskrit.org/www/shukavak.htm Shukavak N. Dasa]</ref> According to Sarkar, "Ahiḿsá means not inflicting pain or hurt on anybody by thought, word or action."<ref name=GTHC/> |

| | |

| There is a debate on the origins of the word ''Ahimsa'', and how its meaning evolved. Mayrhofer as well as Dumot suggest the root word may be ''han'' which means kill, which leads to the interpretation that ''ahimsa'' means ''do not kill''. Schmidt as well as Bodewitz explain the proper root word is ''hiṃs'' and the Sanskrit verb ''hinasti'', which leads to the interpretation ''ahimsa'' means ''do not injure'', or ''do not hurt''. Wackernagel-Debrunner concur with the latter explanation.<ref name=houben>Henk Bodewitz (in Jan E. M. Houben, Karel Rijk van Kooij, Eds.), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History, ISBN 978-9004113442, Brill Academic Pub (June 1999), see Chapter 2</ref><ref name="XXII-XLVII 1986, p. 11-12">Walli pp. XXII-XLVII; Borman, William: ''Gandhi and Non-Violence'', Albany 1986, p. 11-12.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Ancient texts use ahimsa to mean non-injury, a broader concept than non-violence. Non-injury implies not killing others, as well as not hurting others mentally or verbally; it includes avoiding all violent means - including physical violence - anything that injures others. In classical Sanskrit literature of Hinduism, another word ''Adrohi'' is sometimes used instead of ''Ahimsa'', as one of the cardinal virtues necessary for moral life. One example is in [[Baudhayana]] Dharmasutra 2.6.23: वाङ्-मनः-कर्म-दण्डैर् भूतानाम् अद्रोही (One who does not injure others with words, thoughts or acts is named ''Adrohi'').<ref name=houben/><ref>[http://sanskritlibrary.org/tomcat/sl/TextViewer?format=0&name=baudhdhs&title=The+Baudhayana-Dharmasūtra&texttype=%2F Baudhayana Dharmasutra 2.6]</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Hinduism==

| |

| | |

| ===Ancient Vedic Texts===

| |

| Ahimsa as an ethical concept evolves in Vedic texts.<ref name=chapple1990/><ref>Walli, Koshelya: ''The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought'', Varanasi 1974, p. 113-145.</ref> The oldest scripts, dated to be before 1000 BC, along with discussing ritual animal sacrifices, indirectly mention Ahimsa, but do not emphasize it. Over time, the Hindu scripts revise ritual practices and the concept of Ahimsa is increasingly refined and emphasized, ultimately Ahimsa becomes the concept that describes the highest virtue by the late Vedic era (about 500 BC). For example, one passage in the oldest Rig Veda reads, "do not harm anything";<ref>''The Hindu history'' By Akshoy Kumar Mazumdar</ref> later, the [[Yajurveda|Yajur Veda]] dated to be between 1000 BC and 600 BC, states, "may all beings look at me with a friendly eye, may I do likewise, and may we look at each other with the eyes of a friend".<ref name=chapple1990/><ref>[http://ebooks.gutenberg.us/himalayanacademy/sacredhinduliterature/lws/lws_ch-39.html To do no harm] Project Gutenberg, see translation for Yajurveda 36.18 VE</ref>

| |

| | |

| The term ''Ahimsa'' appears in the text [[Taittiriya Shakha]] of the [[Yajurveda]] (TS 5.2.8.7), where it refers to non-injury to the sacrificer himself.<ref>Tähtinen p. 2.</ref> It occurs several times in the ''[[Shatapatha Brahmana]]'' in the sense of "non-injury" without a moral connotation.<ref>Shatapatha Brahmana 2.3.4.30; 2.5.1.14; 6.3.1.26; 6.3.1.39.</ref> The Ahimsa doctrine is a late development in Brahmanical culture.<ref name="houben 1999">Henk M. Bodewitz in Jan E. M. Houben, K. R. van Kooij, ed., ''Violence denied: violence, non-violence and the rationalization of violence in "South Asian" cultural history.'' BRILL, 1999 page 30.</ref> The earliest reference to the idea of non-violence to animals ("pashu-Ahimsa"), apparently in a moral sense, is in the Kapisthala Katha Samhita of the Yajurveda (KapS 31.11), which may have been written in about the 8th century BCE.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 2–3.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Bowker claims the word scarcely appears in the principal Upanishads.<ref>John Bowker, ''Problems of suffering in religions of the world.'' Cambridge University Press, 1975, page 233.</ref> Kaneda gives examples of the word ''Ahimsa'' in Upanishads.<ref name=kaneda2008>Kaneda, T. (2008). Shanti, peacefulness of mind. C. Eppert & H. Wang (Eds.), Cross cultural studies in curriculum: Eastern thought, educational insights, pages 171-192, ISBN 978-0805856736, Taylor & Francis</ref> Other scholars<ref name=arapura>John Arapura in K. R. Sundararajan and Bithika Mukerji Ed. (1997), Hindu spirituality: Postclassical and modern, ISBN 978-8120819375; see Chapter 20, pages 392-417</ref><ref>Izawa, A. (2008). Empathy for Pain in Vedic Ritual. Journal of the International College for Advanced Buddhist Studies, 12, 78</ref> suggest ''Ahimsa'' as an ethical concept that started evolving in the Vedas, became an increasingly central concept in Upanishads.

| |

| | |

| The [[Chāndogya Upaniṣad]], dated to the 8th or 7th century BCE, one of the oldest [[Upanishads]], has the earliest evidence for the use of the word ''Ahimsa'' in the sense familiar in Hinduism (a code of conduct). It bars violence against "all creatures" (''sarvabhuta'') and the practitioner of Ahimsa is said to escape from the cycle of [[metempsychosis]] (CU 8.15.1).<ref>Tähtinen pp. 2–5; English translation: Schmidt p. 631.</ref> A few scholars are of the opinion that this passage was a concession to growing influence of [[Shramana|shramanic]] culture, primarily Jainism, on the Brahmanical religion.<ref>Puruṣottama Bilimoria, Joseph Prabhu, Renuka M. Sharma, ''Indian Ethics: Classical traditions and contemporary challenges.'' Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007, page 315.</ref><ref>Bal Gangadhar Tilak, “Bombay Samachar”. Mumbai:10 Dec, 1904</ref></cite>

| |

| | |

| Chāndogya Upaniṣad also names Ahimsa, along with Satyavacanam (truthfulness), Arjavam (sincerity), [[Dāna|Danam]] (charity), [[Tapas (Sanskrit)|Tapo]] (penance/meditation), as one of five essential virtues (CU 3.17.4).<ref name=arapura/><ref>Ravindra Kumar (2008), Non-violence and Its Philosophy, ISBN 81-7933-159-9, see page 11-14</ref>

| |

| | |

| The Sandilya [[Upanishad]] lists ten forbearances: '''Ahimsa''', Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Daya, Arjava,Kshama, Dhriti, Mitahara and Saucha.<ref>Swami, P. (2000). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upaniṣads: SZ (Vol. 3). Sarup & Sons; see pages 630-631</ref><ref>Ballantyne, J. R., & Yogīndra, S. (1850). A Lecture on the Vedánta: Embracing the Text of the Vedánta-sára. Presbyterian mission press.</ref> According to Kaneda,<ref name=kaneda2008/> the term Ahimsa is an important spiritual doctrine shared by Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. It literally means 'non-injury' and 'non-killing'. It implies the total avoidance of harming of any kind of living creatures not only by deeds, but also by words and in thoughts.

| |

| | |

| ===The Epics===

| |

| The [[Mahabharata]], one of the epics of Hinduism has multiple mentions of the phrase ''Ahimsa Paramo Dharma'' (अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मः), which literally means: non-violence is the highest moral virtue. For example, [[Mahaprasthanika Parva]] has the verse:<ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/mbs/mbs13117.htm Mahabharata 13.117.37-38]</ref>

| |

| <blockquote><poem>

| |

| अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मस तथाहिंसा परॊ दमः | अहिंसा परमं दानम अहिंसा परमस तपः | अहिंसा परमॊ यज्ञस तथाहिस्मा परं बलम | अहिंसा परमं मित्रम अहिंसा परमं सुखम | अहिंसा परमं सत्यम अहिंसा परमं शरुतम ||

| |

| </poem></blockquote>

| |

| The above passage from Mahabharata emphasizes the cardinal importance of Ahimsa in Hinduism, and literally means: Ahimsa is the highest [[virtue]], Ahimsa is the highest self-control, Ahimsa is the greatest gift, Ahimsa is the best suffering, Ahimsa is the highest sacrifice, Ahimsa is the finest strength, Ahimsa is the greatest friend, Ahimsa is the greatest happiness, Ahimsa is the highest truth, and Ahimsa is the greatest teaching.<ref>Chapple, C. (1990). Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition. In Perspectives on Nonviolence (pp. 168-177). Springer New York.</ref><ref>[http://www.hinduismtoday.com/pdf_downloads/what_is_hinduism/Sec6/WIH_Sec6_Chapter45.pdf Ahimsa: To do no harm] Subramuniyaswami, What is Hinduism?, Chapter 45, Pages 359-361</ref> Some other examples where the phrase ''Ahimsa Paramo Dharma'' are discussed include [[Adi Parva]], [[Vana Parva]] and [[Anushasana Parva]]. The [[Bhagavad Gita]], among other things, discusses the doubts and questions about appropriate response when one faces systematic violence or war. These verses develop the concepts of lawful violence in self-defense and the [[Just war theory|theories of just war]]. However, there is no consensus on this interpretation. Gandhi, for example, considers this debate about non-violence and lawful violence as a mere metaphor for the internal war within each human being, when he or she faces moral questions.<ref name=fischer1954/>

| |

| | |

| ===Self-defense, criminal law, and war===

| |

| The classical texts of Hinduism devote numerous chapters discussing what people who practice the virtue of Ahimsa, can and must do when they are faced with war, violent threat or need to sentence someone convicted of a crime. These discussions have led to theories of just war, theories of reasonable self-defense and theories of proportionate punishment.<ref name=balkaran2012/><ref name=klos1996>Klaus K. Klostermaier (1996), in Harvey Leonard Dyck and Peter Brock (Ed), The Pacifist Impulse in Historical Perspective, see ''Chapter on Himsa and Ahimsa Traditions in Hinduism'', ISBN 978-0802007773, University of Toronto Press, pages 230-234</ref> [[Arthashastra]] discusses, among other things, why and what constitutes proportionate response and punishment.<ref name=robinson2003>Paul F. Robinson (2003), Just War in Comparative Perspective, ISBN 0-7546-3587-2, Ashgate Publishing, see pages 114-125</ref><ref>Coates, B. E. (2008). Modern India's Strategic Advantage to the United States: Her Twin Strengths in Himsa and Ahimsa. Comparative Strategy, 27(2), pages 133-147</ref>

| |

| | |

| ;War

| |

| The precepts of Ahimsa under Hinduism require that war must be avoided, with sincere and truthful dialogue. Force must be the last resort. If war becomes necessary, its cause must be just, its purpose virtuous, its objective to restrain the wicked, its aim peace, its method lawful.<ref name=balkaran2012/><ref name=robinson2003/> War can only be started and stopped by a legitimate authority. Weapons used must be proportionate to the opponent and the aim of war, not indiscriminate tools of destruction.<ref>Subedi, S. P. (2003). The Concept in Hinduism of ‘Just War’. Journal of Conflict and Security Law, 8(2), pages 339-361</ref> All strategies and weapons used in the war must be to defeat the opponent, not designed to cause misery to the opponent; for example, use of arrows is allowed, but use of arrows smeared with painful poison is not allowed. Warriors must use judgment in the battlefield. Cruelty to the opponent during war is forbidden. Wounded, unarmed opponent warriors must not be attacked or killed, they must be brought to your realm and given medical treatment.<ref name=robinson2003/> Children, women and civilians must not be injured. While the war is in progress, sincere dialogue for peace must continue.<ref name=balkaran2012/><ref name=klos1996/>

| |

| | |

| ;Self-defense

| |

| In matters of self-defense, different interpretations of ancient Hindu texts have been offered. For example, Tähtinen suggests self-defense is appropriate, criminals are not protected by the rule of Ahimsa, and Hindu scriptures support the use of violence against an armed attacker.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 96, 98–101.</ref><ref>Mahabharata 12.15.55; Manu Smriti 8.349–350; Matsya Purana 226.116.</ref> Ahimsa is not meant to imply pacifism.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 91–93.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Alternate theories of self-defense, inspired by Ahimsa, build principles similar to theories of just war. [[Aikido]], pioneered in Japan, illustrates one such principles of self-defense. [[Morihei Ueshiba]], the founder of Aikido, described his inspiration as Ahimsa.<ref>[http://www.sportspa.com.ba/images/dec2011/full/rad8.pdf The Role of Teachers in Martial Arts] Nebojša Vasic, University of Zenica (2011); Sport SPA Vol. 8, Issue 2: 47-51; see page 46, 2nd column</ref> According to this interpretation of Ahimsa in self-defense, one must not assume that the world is free of aggression. One must presume that some people will, out of ignorance, error or fear, attack other persons or intrude into their space, physically or verbally. The aim of self-defense, suggested Ueshiba, must be to neutralize the aggression of the attacker, and avoid the conflict. The best defense is one where the victim is protected, as well as the attacker is respected and not injured if possible. Under Ahimsa and Aikido, there are no enemies, and appropriate self-defense focuses on neutralizing the immaturity, assumptions and aggressive strivings of the attacker.<ref>[http://aiki-extensions.org/pubs/conflict-body_text.pdf SOCIAL CONFLICT, AGGRESSION, AND THE BODY IN EURO-AMERICAN AND ASIAN SOCIAL THOUGHT] Donald Levine, University of Chicago (2004)</ref><ref>Ueshiba, Kisshōmaru (2004), ''The Art of Aikido: Principles and Essential Techniques'', Kodansha International, ISBN 4-7700-2945-4</ref>

| |

| | |

| ;Criminal law

| |

| Tähtinen concludes that Hindus have no misgivings about death penalty; their position is that evil-doers who deserve death should be killed, and that a king in particular is obliged to punish criminals and should not hesitate to kill them, even if they happen to be his own brothers and sons.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 96, 98–99.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Other scholars<ref name=klos1996/><ref name=robinson2003/> conclude that the scriptures of Hinduism suggest sentences for any crime must be fair, proportional and not cruel.

| |

| | |

| ;Pacifism

| |

| There is no universal consensus on [[pacifism]] among Hindu scholars of modern times. The conflict between pacifistic interpretations of Ahimsa and the theories of [[just war]] prescribed by the Gita has been resolved by some scholars such as [[Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi]], as being an allegory,<ref>Gandhi, Mohandas K., ''The Bhagavad Gita According to Gandhi'' Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley 2000</ref> wherein the battlefield is the soul and Arjuna, the war is within each human being, where man's higher impulses struggle against his own evil impulses.<ref name=fischer1954>Fischer, Louis: ''Gandhi: His Life and Message to the World'' Mentor, New York 1954, pp. 15–16</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Non-human life===

| |

| The Hindu precept of 'cause no injury' applies to animals and all life forms. This precept isn’t found in the oldest verses of Vedas, but increasingly becomes one of the central ideas between 500 BC and 400 AD.<ref name=chapple16>Christopher Chapple (1993), Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1498-1, pages 16-17</ref><ref>W Norman Brown (February 1964), [http://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1964_16/5-6-7/the_sanctity_of_the_cow_in_hinduism.pdf ‘‘The sanctity of the cow in Hinduism’’], The Economic Weekly, pages 245-255</ref> In the oldest texts, numerous ritual sacrifices of animals, including cows and horses, are highlighted and hardly any mention is made of Ahimsa to non-human life.<ref>D.N. Jha (2002), ‘‘The Myth of the Holy Cow’’, ISBN 1859846769, Verso</ref><ref>Steven Rosen (2004), Holy Cow: The Hare Krishna Contribution to Vegetarianism and Animal Rights, ISBN 1-59056-066-3, pages 19-39</ref>

| |

| | |

| Hindu scriptures, dated to between 5th century and 1st century BC, while discussing human diet, initially suggest ‘‘kosher’’ meat may be eaten, evolving it with the suggestion that only meat obtained through ritual sacrifice can be eaten, then that one should eat no meat because it hurts animals, with verses describing the noble life as one that lives on flowers, roots and fruits alone.<ref name=chapple16/><ref>[[Baudhayana]] Dharmasutra 2.4.7; 2.6.2; 2.11.15; 2.12.8; 3.1.13; 3.3.6; [[Apastamba]] Dharmasutra 1.17.15; 1.17.19; 2.17.26–2.18.3; Vasistha Dharmasutra 14.12.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Later texts of Hinduism declare Ahimsa one of the primary virtues, declare any killing or harming any life as against ‘‘dharma’’ (moral life). Finally, the discussion in Upanishads and Hindu Epics<ref>Manu Smriti 5.30, 5.32, 5.39 and 5.44; Mahabharata 3.199 (3.207), 3.199.5 (3.207.5), 3.199.19-29 (3.207.19), 3.199.23–24 (3.207.23–24), 13.116.15–18, 14.28; Ramayana 1-2-8:19</ref> shifts to whether a human being can ever live his or her life without harming animal and plant life in some way; which and when plants or animal meat may be eaten, whether violence against animals causes human beings to become less compassionate, and if and how one may exert least harm to non-human life consistent with ahimsa precept, given the constraints of life and human needs.<ref>Alsdorf pp. 592–593.</ref><ref>Mahabharata 13.115.59–60; 13.116.15–18.</ref> The Mahabharata permits hunting by warriors, but opposes it in the case of hermits who must be strictly non-violent. [[Sushruta Samhita]], a Hindu text written in the 3rd or 4th century, in Chapter XLVI suggests proper diet as a means of treating certain illnesses, and recommends various fishes and meats for different ailments and for pregnant women,<ref>Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna (1907), An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita, Volume I, Part 2; see Chapter starting on page 469; for discussion on meats and fishes, see page 480 and onwards</ref><ref>Sutrasthana 46.89; Sharirasthana 3.25.</ref> and the [[Charaka Samhita]] describes meat as superior to all other kinds of food for convalescents.<ref>Sutrasthana 27.87.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Across the texts of Hinduism, there is a profusion of ideas about the virtue of Ahimsa when applied to non-human life, but without a universal consensus.<ref>Mahabharata 3.199.11–12 (3.199 is 3.207 elsewhere); 13.115; 13.116.26; 13.148.17; Bhagavata Purana (11.5.13–14), and the Chandogya Upanishad (8.15.1).</ref> Alsdorf claims the debate and disagreements between supporters of vegetarian lifestyle and meat eaters was significant. Even suggested exceptions – ritual slaughter and hunting – were challenged by advocates of Ahimsa.<ref>Alsdorf pp. 572–577 (for the Manusmṛti) and pp. 585–597 (for the Mahabharata); Tähtinen pp. 34–36.</ref><ref>The Mahabharata and the Manusmṛti (5.27–55) contain lengthy discussions about the legitimacy of ritual slaughter.</ref><ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m12/m12b095.htm Mahabharata 12.260] (12.260 is 12.268 according to another count); 13.115–116; 14.28.</ref> In the Mahabharata both sides present various arguments to substantiate their viewpoints. Moreover, a hunter defends his profession in a long discourse.<ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m03/m03207.htm Mahabharata 3.199] (3.199 is 3.207 according to another count).</ref>

| |

| | |

| Many of the arguments proposed in favor of non-violence to animals refer to the bliss one feels, the rewards it entails before or after death, the danger and harm it prevents, as well as to the karmic consequences of violence.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 39–43.</ref><ref>Alsdorf p. 589-590; Schmidt pp. 634–635, 640–643; Tähtinen pp. 41–42.</ref>

| |

| | |

| The ancient Hindu texts discuss Ahimsa and non-animal life. They discourage wanton destruction of nature including of wild and cultivated plants. Hermits ([[sannyasa|sannyasin]]s) were urged to live on a [[fruitarian]] diet so as to avoid the destruction of plants.<ref>Schmidt pp. 637–639; Manusmriti 10.63, 11.145</ref><ref>Rod Preece, Animals and Nature: Cultural Myths, Cultural Realities, ISBN 978-0-7748-0725-8, University of British Columbia Press, pages 212-217</ref> Scholars<ref>Chapple, C. (1990). Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition. In ‘’Perspectives on Nonviolence’’ (pages 168-177). Springer New York</ref><ref>Van Horn, G. (2006). Hindu Traditions and Nature: Survey Article. Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 10(1), 5-39</ref> claim the principles of ecological non-violence is innate in the Hindu tradition, and its conceptual fountain has been Ahimsa as their cardinal virtue.

| |

| | |

| The classical literature of Hinduism exists in many Indian languages. For example, ''[[Tirukkuṛaḷ]]'' written between 200 BC and 400 AD, and sometimes called the Tamil [[Veda]], is one of the most cherished classics on Hinduism written in a South Indian language. Tirukkuṛaḷ dedicates Chapter 32 and 33 of Book 1 to the virtue of Ahimsa. ''Tirukkuṛaḷ'' suggests that Ahimsa applies to all life forms.<ref>[http://www.projectmadurai.org/pm_etexts/pdf/pm0153.pdf Tirukkuṛaḷ] Translated by Rev G.U. Pope, Rev W.H. Drew, Rev John Lazarus, and Mr F W Ellis (1886), WH Allen & Company; see pages 40-41, verses 311-330</ref><ref>[http://ebooks.gutenberg.us/HimalayanAcademy/SacredHinduLiterature/weaver/content.htm Tirukkuṛaḷ] see Chapter 32 and 33, Book 1</ref><ref>[http://www.worldcat.org/title/tirukkural-tirukkural/oclc/777453934?referer=di&ht=edition Tirukkuṛaḷ] Translated by V.V.R. Aiyar, Tirupparaithurai : Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam (1998)</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Modern times===

| |

| [[File:Portrait Gandhi.jpg|thumb|[[Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi|Gandhi]] promoted the principle of Ahimsa very successfully by applying it to all spheres of life, particularly to politics.]]

| |

| | |

| In modern Hinduism slaughter according to the rituals permitted in the Vedic scriptures has become less common, though, the world's largest animal sacrifice occurs at Gadhimai ([[Nepal]]), a Hindu festival which takes place every 5 years.<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/nov/24/hindu-sacrifice-gadhimai-festival-nepal Hindu sacrifice of 250,000 animals begins]</ref> In the 19th and 20th centuries, prominent figures of Indian spirituality such as [[Swami Vivekananda]],<ref>''Religious Vegetarianism'', ed. [[Kerry S. Walters]] and Lisa Portmess, Albany 2001, p. 50-52.</ref> [[Ramana Maharshi]],<ref>[http://www.beasyouare.info/beasyouare.html Ramana Maharishi: ''Be as you are'']. Beasyouare.info. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> [[Swami Sivananda]],<ref>[http://www.dlshq.org/teachings/ahimsa.htm Swami Sivananda: ''Bliss Divine'', p. 3-8]. Dlshq.org (2005-12-11). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> [[A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami]]<ref>''Religious Vegetarianism'' p. 56-60.</ref> and in the present time Vijaypal Baghel emphasized the importance of Ahimsa.

| |

| | |

| [[Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi]] promoted the principle of Ahimsa very successfully by applying it to all spheres of life, particularly to politics ([[Swaraj]]).<ref>Tähtinen pp. 116–124.</ref> His non-violent resistance movement [[satyagraha]] had an immense impact on India, impressed public opinion in Western countries and influenced the leaders of various [[civil and political rights]] movements such as [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] In Gandhi’s thought, Ahimsa precludes not only the act of inflicting a physical injury, but also mental states like evil thoughts and hatred, unkind behavior such as harsh words, dishonesty and lying, all of which he saw as manifestations of violence incompatible with Ahimsa.<ref name="XXII-XLVII 1986, p. 11-12"/> Gandhi believed Ahimsa to be a creative energy force, encompassing all interactions leading one's self to find satya, "Divine Truth".<ref>Jackson pp.39-54. Religion East & West. 2008.</ref> [[Sri Aurobindo]] criticized the Gandhian concept of Ahimsa as unrealistic and not universally applicable; he adopted a pragmatic non-pacifist position, saying that the justification of violence depends on the specific circumstances of the given situation.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 115–116.</ref> Sri Aurobindo also indicated that Gandhi's Ahimsa led to partition of India as it blocked the forceful action that the Indian people were engaged in in the 1920s and 30s, which caused delay in independence, allowing other forces to take root, including those who wanted India divided.

| |

| | |

| A thorough historical and philosophical study of Ahimsa was instrumental in the shaping of [[Albert Schweitzer]]'s principle of "reverence for life". Schweitzer criticized Indian philosophical and religious traditions for having conceived Ahimsa as the negative principle of avoiding violence instead of emphasizing the importance of positive action (helping injured beings).<ref>Schweitzer, Albert: ''Indian Thought and its Development'', London 1956, p. 80-84, 100–104, 110–112, 198–200, 223–225, 229–230.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Yoga===

| |

| Ahimsa is imperative for practitioners of [[Patañjali]]’s "classical" Yoga ([[Raja Yoga]]). It is one of the five [[Yamas]] (restraints) which make up the code of conduct, the first of the eight limbs of which this path consists.<ref>Patañjali: ''Yoga Sutras'', Sadhana Pada 30.</ref> In the schools of [[Bhakti Yoga]], the devotees who worship [[Vishnu]] or Krishna are particularly keen on Ahimsa.<ref>Tähtinen p. 87.</ref> Another [[Bhakti Yoga]] school, [[Radha Soami Satsang Beas]] observes vegetarianism and moral living as aspects of "Ahimsa."

| |

| Ahimsa is also an obligation in [[Hatha Yoga]] according to the classic manual [[Hatha Yoga Pradipika]] (1.1.17). But it is important to note that Ahmisa as used here is distinct from that in Jainism. Yagnas and mantras are prescribed for attaining glory in Vedas.

| |

| | |

| ==Jainism==

| |

| {{Main|Ahimsa in Jainism}}

| |

| [[File:Jain hand.svg|thumb|right|150px|The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes the Jain Vow of Ahimsa. The word in the middle is "Ahimsa". The wheel represents the [[dharmacakra]] which stands for the resolve to halt the cycle of reincarnation through relentless pursuit of truth and non-violence.]]

| |

| In Jainism, the understanding and implementation of Ahimsa is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in any other religion.<ref>Laidlaw, pp. 154–160; Jindal, pp. 74–90; Tähtinen p. 110.</ref> Non-violence is seen as the most essential religious duty for everyone (''{{IAST|ahiṃsā paramo dharmaḥ}}'', a statement often inscribed on Jain temples).<ref>Dundas, Paul: ''The Jains'', second edition, London 2002, p. 160; Wiley, Kristi L.: ''Ahimsa and Compassion in Jainism'', in: ''Studies in Jaina History and Culture'', ed. Peter Flügel, London 2006, p. 438; Laidlaw pp. 153–154.</ref> Like in Hinduism, the aim is to prevent the accumulation of harmful karma.<ref>Laidlaw pp. 26–30, 191–195.</ref> When [[Mahavira]] revived and reorganized the Jain movement in the 6th or 5th century BCE,<ref>Dundas p. 24 suggests the 5th century; the traditional dating of Mahavira’s death is 527 BCE.</ref> Ahimsa was already an established, strictly observed rule.<ref>Goyal, S.R.: ''A History of Indian Buddhism'', Meerut 1987, p. 83-85.</ref> [[Parshva]], the earliest Jain [[Tirthankara]], whom modern Western historians consider to be a historical figure,<ref>Dundas pp. 19, 30; Tähtinen p. 132.</ref> lived in about the 8th century BCE.<ref>Dundas p. 30 suggests the 8th or 7th century; the traditional chronology places him in the late 9th or early 8th century.</ref> He founded the community to which Mahavira’s parents belonged.<ref>[[Acaranga Sutra]] 2.15.</ref> Ahimsa was already part of the "Fourfold Restraint" (''Caujjama''), the vows taken by Parshva’s followers.<ref>[[Sthananga Sutra]] 266; Tähtinen p. 132; Goyal p. 83-84, 103.</ref> In the times of Mahavira and in the following centuries, Jains were at odds with both Buddhists and followers of the Vedic religion or Hindus, whom they accused of negligence and inconsistency in the implementation of Ahimsa.<ref>Dundas pp. 160, 234, 241; Wiley p. 448; Granoff, Phyllis: ''The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices'', in: ''Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies'' 15 (1992) pp. 1–43; Tähtinen pp. 8–9.</ref> There is some evidence, however, that ancient Jain ascetics accepted meat as alms if the animal had not been specifically killed for them.<ref>Alsdorf pp. 564–570; Dundas p. 177.</ref> Modern Jains deny this vehemently, especially with regard to Mahavira himself.<ref>Alsdorf pp. 568–569.</ref> According to the Jain tradition either [[lacto vegetarianism]] or [[veganism]] is mandatory.<ref>Laidlaw p. 169.</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

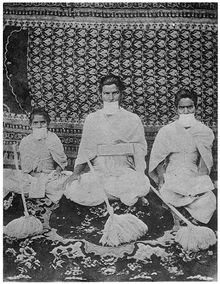

| The Jain concept of Ahimsa is characterized by several aspects. It does not make any exception for ritual sacrificers and professional warrior-hunters. Killing of animals for food is absolutely ruled out.<ref>Laidlaw pp. 166–167; Tähtinen p. 37.</ref> Jains also make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life as far as possible. Though they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants.<ref>Lodha, R.M.: ''Conservation of Vegetation and Jain Philosophy'', in: ''Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment'', New Delhi 1990, p. 137-141; Tähtinen p. 105.</ref> Jains go out of their way so as not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals.<ref>Jindal p. 89; Laidlaw pp. 54, 154–155, 180.</ref> For example, Jains often do not go out at night, when they are more likely to step upon an insect. In their view, injury caused by carelessness is like injury caused by deliberate action.<ref>Sutrakrtangasutram 1.8.3; Uttaradhyayanasutra 10; Tattvarthasutra 7.8; Dundas pp. 161–162.</ref> Eating honey is strictly outlawed, as it would amount to violence against the bees.<ref>[[Hemacandra]]: ''Yogashastra'' 3.37; Laidlaw pp. 166–167.</ref> Some Jains abstain from farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of many small animals, such as worms and insects,<ref>Laidlaw p. 180.</ref> but agriculture is not forbidden in general and there are Jain farmers.<ref>Sangave, Vilas Adinath: ''Jaina Community. A Social Survey'', second edition, Bombay 1980, p. 259; Dundas p. 191.</ref> Additionally, because they consider harsh words to be a form of violence, they often keep a cloth to ritually cover their mouth, as a reminder not to allow violence in their speech.

| | There is a debate on the origins of the word ''Ahimsa'', and how its meaning evolved. Mayrhofer as well as Dumot suggest the root word may be ''han'' which means kill, which leads to the interpretation that ''ahimsa'' means ''do not kill''. Schmidt as well as Bodewitz explain the proper root word is ''hiṃs'' and the Sanskrit verb ''hinasti'', which leads to the interpretation that ''ahimsa'' means ''do not injure'', or ''do not hurt''. Wackernagel-Debrunner (and Sarkar) concur with the latter explanation.<ref name=houben>Henk Bodewitz (in Jan E. M. Houben, Karel Rijk van Kooij, Eds.), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History, ISBN 978-9004113442, Brill Academic Pub (June 1999), see Chapter 2</ref><ref name="XXII-XLVII 1986, p. 11-12">Walli pp. XXII-XLVII; Borman, William: ''Gandhi and Non-Violence'', Albany 1986, p. 11-12.</ref> |

|

| |

|

| In contrast, Jains agree with Hindus that violence in self-defense can be justified,<ref>''Nisithabhasya'' (in ''Nisithasutra'') 289; Jinadatta Suri: ''Upadesharasayana'' 26; Dundas pp. 162–163; Tähtinen p. 31.</ref> and they agree that a soldier who kills enemies in combat is performing a legitimate duty.<ref>Jindal pp. 89–90; Laidlaw pp. 154–155; Jaini, Padmanabh S.: ''Ahimsa and "Just War" in Jainism'', in: ''Ahimsa, Anekanta and Jainism'', ed. Tara Sethia, New Delhi 2004, p. 52-60; Tähtinen p. 31.</ref> Jain communities accepted the use of military power for their defense, and there were Jain monarchs, military commanders, and soldiers.<ref>Harisena, ''Brhatkathakosa'' 124 (10th century); Jindal pp. 90–91; Sangave p. 259.</ref>

| | ==History== |

| | {{Yama-Niyama}} |

| | The concept of ahimsa first arose as an ethical precept in the indigenous tantric tradition of ancient India. Over time, the concept of ahimsa made its way into Vedic texts with varying interpretations. When the philosopher [[:wikipedia:Patanjali|Patanjali]] (circa 200-400BCE) systematized tantra into what is popularly known as ''Aśt́áuṋga Yoga'' (eight-limbed yoga) or ''Rája Yoga'' (the king of yogas), ahimsa was the first principle of his first element of yoga, ''Yama''.<ref>Patañjali: ''Yoga Sutras'', Sadhana Pada 30.</ref> |

|

| |

|

| Though, theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, Jains admit that this ideal cannot be completely implemented in practice. Hence, they recognize a hierarchy of life. Mobile beings are given higher protection than immobile ones. For the mobile beings, they distinguish between one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed and five-sensed ones; a one-sensed animal has touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more they care about its protection. Among the five-sensed beings, the rational ones (humans) are most strongly protected by Jain Ahimsa.<ref>Jindal pp. 89, 125–133 (detailed exposition of the classification system); Tähtinen pp. 17, 113.</ref> In the practice of Ahimsa, the requirements are less strict for the lay persons who have undertaken ''anuvrata'' (Lesser Vows) than for the [[Jain monasticism|monastics]] who are bound by the [[Mahavrata]] "Great Vows".<ref>Dundas pp. 158–159, 189–192; Laidlaw pp. 173–175, 179; ''Religious Vegetarianism'', ed. [[Kerry S. Walters]] and Lisa Portmess, Albany 2001, p. 43-46 (translation of the First Great Vow).</ref>

| | ==Various interpretations of Ahimsa== |

| | [[File:Sthanakvasi monks.jpg|left|thumb|220px|Some Jain monks wear a mask over their mouth]] |

| | In both [[:wikipedia:Jainism|Jainism]] and [[:wikipedia:Buddhism|Buddhism]], both circa 500BCE, ahimsa is a key ethical principle. In Jainism, it is the first and main ethical principle. Jain renunciates reject the use of force even when it is required for self-defense. They are often seen wearing a mask over their mouth to avoid the unintentional ingestion of flies. And they have also been known to pour sugar into anthills.<ref name=GTHC/> Buddhists observe a somewhat less strict interpretation of ahimsa. For example, unlike Jains, not all Buddhists are vegetarian. |

|

| |

|

| ==Buddhism==

| | In modern times, the concept of ahimsa has taken on a new meaning, in large part due to the teachings and activities of [[:wikipedia:Mahatma Gandhi|Mohandas Gandhi]]. According to Gandhi, ahimsa means ''non-violence''. This is perhaps the most extreme interpretation of ahimsa, given the fact that even Jains and Hindus accept the use of violence in self-defense.<ref>''Nisithabhasya'' (in ''Nisithasutra'') 289; Jinadatta Suri: ''Upadesharasayana'' 26; Dundas pp. 162–163; Tähtinen p. 31.</ref><ref>Jindal pp. 89–90; Laidlaw pp. 154–155; Jaini, Padmanabh S.: ''Ahimsa and "Just War" in Jainism'', in: ''Ahimsa, Anekanta and Jainism'', ed. Tara Sethia, New Delhi 2004, p. 52-60; Tähtinen p. 31.</ref> |

| Unlike in Hindu and Jain sources, in ancient Buddhist texts ''Ahimsa'' (or its [[Pāli]] cognate {{IAST|avihiṃsā}}) is not used as a technical term.<ref>Tähtinen p. 10.</ref> The traditional Buddhist understanding of non-violence is not as rigid as the Jain one, but like the Jains, Buddhists have always condemned the killing of all living beings.<ref>Sarao, p. 49; Goyal p. 143; Tähtinen p. 37.</ref><ref name="Lamotte, Etienne 1988, p. 54-55">Lamotte, pp. 54–55.</ref> In some Buddhist traditions vegetarianism is not mandatory. In these traditions, monks and lay persons may eat meat and fish on condition that the animal was not killed specifically for them.<ref>Sarao pp. 51–52; Alsdorf pp. 561–564.</ref> For some monks, specifically monks of some Mahayana traditions, the eating of meat is strictly forbidden. Laypeople are also encouraged to eat vegetarian.

| |

|

| |

|

| Since the beginnings of the Buddhist community, monks and nuns have had to commit themselves to the [[Five Precepts]] of moral conduct.<ref name="Lamotte, Etienne 1988, p. 54-55"/> In ancient Buddhism, lay persons were encouraged, but not obliged, to commit themselves to observe the Five Precepts of morality ({{IAST|Pañcasīla}}).<ref>Lamotte pp. 69–70.</ref> In both codes the first rule is to abstain from taking the life of a sentient being ({{IAST|Pānātipātā}}).<ref>Lamotte p. 70.</ref> Buddhist monks should avoid cutting or burning trees, because some sentient beings rely on them.<ref>[http://www.awker.com/hongshi/mag/82/82-10.htm 從律典探索佛教對動物的態度(中)]. Awker.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref>

| | ==Sarkar on ahimsa== |

| | According to Sarkar, principles of morality must take into account both action and intent. When there is an unavoidable conflict between the two, intent becomes primary. So Sarkar notes with respect to ahimsa that violence (or the use of force) is both natural and unavoidable. Hence, ahimsa cannot be reasonably interpreted to mean the non-use of force.<ref name=GTHC/> |

|

| |

|

| ===War===

| | Life feeds on life. So, for example, our choice is to drink purified or unpurified water. In both instances, we end up killing microbes, either outside or inside our body. Hence, with respect to food, Sarkar endorsed a gradation rule, similar to that of the Jains, whereby food is selected with an effort to maintain a healthy body and mind by taking sustenance from entities with the least self-awareness. When it is possible to remain healthy by subsisting on grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, nuts and the like, then there is no justification for killing animals or even fish to eat their flesh.<ref name=GTHC/> |

| Unlike the Vedic religion, ancient Buddhism had strong misgivings about violent ways of punishing criminals and war. Neither was explicitly condemned,<ref>Sarao p. 53; Tähtinen pp. 95, 102.</ref> but peaceful ways of conflict resolution and punishment with the least amount of injury were encouraged.<ref>Tähtinen pp. 95, 102–103.</ref><ref>Kurt A. Raaflaub, [http://books.google.com/books?id=FMxgef2VJEwC&pg=PA61 ''War and Peace in the Ancient World.''] Blackwell Publishing, 2007 , p. 61.</ref> The early texts condemn the mental states that lead to violent behavior.<ref>Bartholomeusz, p. 52.</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| Non-violence is an over-riding concern of the [[Pali Canon]].<ref>Bartholomeusz, p. 111.</ref> While the early texts condemn killing in the strongest terms, and portray the ideal king as a pacifist, such a king is nonetheless flanked by an army.<ref name="Tessa Bartholomeusz 2002, page 41">Bartholomeusz, p. 41.</ref> It seems that the Buddha's teaching on non-violence was not interpreted or put into practice in an uncompromisingly pacifist or anti-military-service way by early Buddhists.<ref name="Tessa Bartholomeusz 2002, page 41"/> The early texts assume war to be a fact of life, and well-skilled warriors are viewed as a necessity for defensive warfare.<ref>Bartholomeusz, p. 50.</ref> In Pali texts, injunctions to abstain from violence and involvement with military affairs are directed at members of the [[sangha]]; later Mahayana texts, which often generalize monastic norms to laity, require this of lay people as well.<ref>Stewart McFarlane in Peter Harvey, ed., ''Buddhism.'' Continuum, 2001, pages 195–196.</ref>

| | According to Sarkar, morality does not suppress the natural instinct for survival. So, with respect to self-defense, Sarkar argues that combat against an aggressor (''átatáyii'' in [[Samskrta]]) is not just acceptable but even noble. Sarkar notes that [[:wikipedia:Krishna|Krsna]] encouraged the [[:wikipedia:Pandavas|Pandavas]] to do battle with the [[:wikipedia:Kaurava|Kaoravas]], because they were aggressors.<ref name=GTHC/> |

| | |

| The early texts do not contain just-war ideology as such.<ref>Bartholomeusz, p. 40.</ref> Some argue that a [[suttas|sutta]] in the ''Gamani Samyuttam'' rules out all military service. In this passage, a soldier asks the Buddha if it is true that, as he has been told, soldiers slain in battle are reborn in a heavenly realm. The Buddha reluctantly replies that if he is killed in battle while his mind is seized with the intention to kill, he will undergo an unpleasant rebirth.<ref>Bartholomeusz, pp. 125–126. Full texts of the sutta:[http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn42/sn42.003.than.html].</ref> In the early texts, a person's mental state at the time of death is generally viewed as having an inordinate impact on the next birth.<ref>Rune E.A. Johansson, ''The Dynamic Psychology of Early Buddhism.'' Curzon Press 1979, page 33.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Some Buddhists point to other early texts as justifying defensive war.<ref>Bartholomeusz, pp. 40–53. Some examples are the ''Cakkavati Sihanada Sutta'', the ''Kosala Samyutta'', the ''Ratthapala Sutta'', and the ''Sinha Sutta''. See also page 125. See also Trevor Ling, ''Buddhism, Imperialism, and War.'' George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1979, pages 136–137.</ref> One example is the ''Kosala Samyutta'', in which King [[Pasenadi]], a righteous king favored by the Buddha, learns of an impending attack on his kingdom. He arms himself in defense, and leads his army into battle to protect his kingdom from attack. He lost a battle but won the war. King Pasenadi defeated King [[Ajatasattu]] and captured him alive. He thought that although this King of [[Magadha]] has transgressed against his kingdom, he had not transgressed against him personally, and Ajatasattu is still his nephew. He released Ajatasattu and did not harm him.<ref>Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-331-1.</ref> Upon his return, the Buddha says, among other things, that Pasenadi is "a friend of virtue, acquainted with virtue, intimate with virtue", while the opposite is said of the aggressor, King Ajatasattu.<ref>Bartholomeusz, pp. 49, 52–53.</ref>

| |

| | |

| According to Theravada commentaries, there are five requisite factors that must all be fulfilled for an act to be both an act of killing and to be karmically negative. These are: (1) the presence of a living being, human or animal; (2) the knowledge that the being is a living being; (3) the intent to kill; (4) the act of killing by some means; and (5) the resulting death.<ref>Hammalawa Saddhatissa, ''Buddhist Ethics.'' Wisdom Publications, 1997, pages 60, 159, see also Bartholomeusz page 121.</ref> Some Buddhists have argued on this basis that the act of killing is complicated, and its ethicization is predicated upon intent.<ref>Bartholomeusz, p. 121.</ref> Some have argued that in defensive postures, for example, the primary intention of a soldier is not to kill, but to save, and the act of killing in that situation would have minimal negative karmic repercussions.<ref>Bartholomeusz, pp. 44, 121–122, 124.</ref>

| |

| | |

| According to [[Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar]], the doctrine of Ahimsa does not state "kill not" but rather "love all". Buddha said ''"Love all, so that you may not wish to kill any."'' This is a positive way of stating the principle of Ahimsa. The Buddha's Ahimsa is quite in keeping with his [[middle path]]. To put it differently, the Buddha made a distinction between a principle and a rule. He did not make Ahimsa a matter of rule. He enunciated it as a matter of principle. A principle leaves you freedom to act; a rule does not.<ref>[http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00ambedkar/ambedkar_buddha/04_02.html#03_02 The Buddha and His Dhamma]. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Laws===

| |

| The emperors of [[Sui dynasty]], [[Tang dynasty]] and early [[Song dynasty]] banned killing in Lunar calendar 1st, 5th, and 9th month.<ref>[http://www.bya.org.hk/life/hokfu/new_page_3.htm#34 卷糺 佛教的慈悲觀]. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://www.drnh.gov.tw/www/page/c_book/b14/試探《護生畫集》的護生觀.pdf 試探《護生畫集》的護生觀 高明芳]</ref><ref>[http://flwh.znufe.edu.cn/article_show.asp?id=2788 唐《開元二十五年令•雜令》研究]. Flwh.znufe.edu.cn (2007-02-28). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> [[Wu Zetian|Empress Wu Tse-Tien]] banned killing for more than half a year in 692.<ref>[http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-AN/an2414.htm 「護生」精神的實踐舉隅]. Ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> Some also banned fishing for some time each year.<ref>[http://www.cclw.net/gospel/asking/dmz10w/htm/02.htm 答妙贞十问]. Cclw.net. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref>

| |

| | |

| The King [[Bayinnaung]] of Burma, after conquering the [[Bago, Burma|Bago]] in 1559, the Buddhist King prohibited the practice of [[halal]], specifically, killing food animals in the name of God. He also disallowed the [[Eid al-Adha]] religious sacrifice of cattle. Halal food was also forbidden by king [[Alaungpaya]] in the 18th century.

| |

| | |

| There were bans after death of emperors,<ref>[http://www.bya.org.hk/life/Q&A_2006/Q&A_bya/128_Q.htm 第一二八期 佛法自由談]. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://www.gz.xinhuanet.com/zfpd/2007-07/06/content_10506416.htm 贵阳南明-生态文明城区]. Gz.xinhuanet.com (2007-07-06). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> Buddhist and Taoist prayers,

| |

| <ref>[http://www.bfnn.org/book/books2/1187.htm 虛雲和尚法彙—書問]. Bfnn.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://www.epochtimes.com/b5/7/1/10/n1585679.htm 五朝祈安清醮三重全市茹素三天祈福]. Epochtimes.com (2010-11-18). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> Health concerns<ref>[http://news.dayoo.com/china/gb/content/2001-03/04/content_79160.htm 比利时出现口蹄疫欧陆如临大敌]. News.dayoo.com (2001-03-04). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://www.022net.com/2005/11-5/431555153298272.html 吉林启动禽流感应急预案 长春活禽市场全关闭]. 022net.com (2005-11-05). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://morning.scol.com.cn/2004/08/24/200408245533044456146.htm 阆中古城首接“禁屠令”]. Morning.scol.com.cn (2004-08-24). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> and natural disasters such as after a drought in 1926 summer Shanghai<ref>[http://www.shtong.gov.cn/node2/node4/node2250/node4427/node5560/node9566/index.html 灾异]. shtong.gov.cn</ref> and

| |

| a 8 days ban from August 12, 1959 after the August 7 flood ([[:zh:八七水災|八七水災]]), the last big flood before [[the 88 Taiwan Flood]].<ref>[http://tw.classf0001.urlifelinks.com/css000000039996/cm4k-1241576509-4891-3610.doc 組員:余秉育]{{dead link|date=June 2011}}</ref><ref>[http://www.plela.org/Cmapwork/link/crona1.htm 道安長老年譜]. Plela.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> There was a 3-day ban after the death of [[Chiang Kai-shek]].<ref>[http://www.duilian.cn/News/wangkan3/200701/163.html 陈立夫]{{dead link|date=June 2011}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| People avoid killing during some festivals, like the Taoist [[Ghost Festival]],<ref>[http://www.sx.chinanews.com.cn/2008-08-18/1/69009.html 农历中元节]. Sx.chinanews.com.cn. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref> the [[Nine Emperor Gods Festival]], the [[Vegetarian Festival]] and many others.<ref>[http://www.mxzxw.cn/zwhgz/wszl_16_23.htm 明溪县“禁屠日”习俗的由来]</ref><ref>[http://www.godpp.gov.cn/ctjr_/2006-01/09/content_6004064.htm 滇西独特的禁屠护兽节]. Godpp.gov.cn (2006-01-09). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=「四月六、七、八日禁屠三天」的玄機!!|url=http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Crete/8454/bir3.html|work=|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kmDTvREW|archivedate=2009-10-24|deadurl=yes}}</ref><ref>[http://www.chinesefolklore.org.cn/web/index.php?Page=2&NewsID=3016 建构的节日:政策过程视角下的唐玄宗诞节]. Chinesefolklore.org.cn (2008-02-16). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref><ref>[http://economy.guoxue.com/article.php/2184 我国古代生态保护资料的新发现]. Economy.guoxue.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.</ref>

| |

| | |

| {{clear}}

| |

| | |

| ==See also==

| |

| {{colbegin}}

| |

| *[[Consistent life ethic]]

| |

| *[[Non-violence]]

| |

| *[[Nonresistance]]

| |

| *[[Pacifism]]

| |

| *[[Yamas]]

| |

| *[[Karuṇā]]

| |

| *[[Civil resistance]]

| |

| *[[Gandhism]]

| |

| *[[Satyagraha]]

| |

| *[[Veganism]]

| |

| *[[Vegetarianism and religion]]

| |

| *[[History of vegetarianism]]

| |

| *[[Sumud]]

| |

| {{colend}}

| |

|

| |

|

| ==References== | | ==References== |

| {{Reflist|colwidth=35em}} | | {{Reflist|colwidth=35em}} |

|

| |

|

| ==Bibliography==

| | [[Category:Uncategorized from December 2014]] |

| {{Refbegin}}

| |

| *{{cite book|author=Alsdorf, Ludwig |title=Beiträge zur Geschichte von Vegetarismus und Rinderverehrung in Indien|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=N2SkkgAACAAJ|accessdate=15 June 2011|year=1962|publisher=Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur; in Kommission bei F. Steiner Wiesbaden}}

| |

| *Bartholomeusz, Tessa [http://books.google.com/books?id=0toLUwD6WgUC&printsec=frontcover ''In Defense of Dharma.''] RoutledgeCurzon 2002 ISBN 0-7007-1681-5

| |

| *Jindal, K.B.: ''An epitome of Jainism'', New Delhi 1988 ISBN 81-215-0058-3

| |

| *Laidlaw, James: ''Riches and Renunciation. Religion, economy, and society among the Jains'', Oxford 1995 ISBN 0-19-828031-9

| |

| *Lamotte, Etienne: ''History of Indian Buddhism from the Origins to the Śaka Era'', Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 ISBN 90-6831-100-X

| |

| *Sarao, K.T.S.: ''The Origin and Nature of Ancient Indian Buddhism'', Delhi 1989

| |

| *Schmidt, Hanns Peter: ''The Origin of Ahimsa'', in: ''Mélanges d'Indianisme à la mémoire de Louis Renou'', Paris 1968

| |

| *Tähtinen, Unto: ''Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition'', London 1976 ISBN 0-09-123340-2

| |

| {{Refend}}

| |

| | |

| ==External links==

| |

| {{commons category|Ahimsa}}

| |

| * [http://www.vedabase.net/a/ahimsa Ahimsa quotations from Puranic scripture] (vedabase.net)

| |

| * [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/varun-soni/celebrating-gandhi-at-the_b_746320.html?view=print Gandhi, Hinduism and Non-Violence at the United Nations] by Varun Soni

| |

| | |

| {{Indian Philosophy}}

| |

| | |

| [[Category:Buddhist philosophical concepts]]

| |

| [[Category:Ethical schools and movements]]

| |

| [[Category:Hindu philosophical concepts]]

| |

| [[Category:Jain philosophical concepts]]

| |

| [[Category:Pacifism]]

| |