Ahimsa

|

| Yama (Restraint) | |

|---|---|

| Ahiḿsá (Benignity) | Thinking, speaking, and acting without inflicting pain or harm on another |

| Satya (Benevolence) | Thinking and speaking with goodwill |

| Asteya (Honesty) | Not taking or keeping what belongs to others |

| Brahmacarya (Ideation) | Constant mental association with the Supreme |

| Aparigraha (Frugality) | Non-indulgence in superfluous amenities |

| Niyama (Regulation) | |

| Shaoca (Cleanliness) | Physical and mental purity, both internal and external |

| Santośa (Contentment) | Maintaining a state of mental ease |

| Tapah (Sacrifice) | Acceptance of sufferings to reach the spiritual goal |

| Svádhyáya (Contemplation) | Clear understanding of any spiritual subject |

| Iishvara Prańidhána (Dedication) | Adopting the Cosmic Controller as the only ideal of life and moving with ever-accelerating speed toward that Desideratum |

| Intent is primary, but both intent and action should conform if possible. | |

Ahimsa (Sanskrit: अहिंसा; IAST: ahiṃsā, Pāli:[1] avihiṃsā) is a term meaning benignity, non-injury. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root hiṃs – to strike. Hiṃsā is injury or harm. A-hiṃsā is the opposite.[2][3]

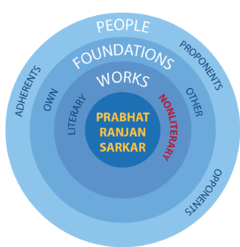

Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues[4], the first of ten principles in the ancient tantric/yogic system of morality, Yama-Niyama. As such, it is also an important tenet of major Indian religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism). Over the years, Ahimsa has been interpreted in many different ways. In his book, A Guide to Human Conduct, Sarkar analyzes the concept of Ahimsa and some popular interpretations of the term.[5]

Etymology

The word Ahimsa - sometimes spelled as Ahinsa[6][7] - is derived from the Sanskrit root hiṃs – to strike; hiṃsā (or hiḿsá in Sarkar's Roman Sanskrit) is injury or harm, a-hiṃsā is the opposite of this, that is benignity or non-jury.[6][8] According to Sarkar, "Ahiḿsá means not inflicting pain or hurt on anybody by thought, word or action."[5]

There is a debate on the origins of the word Ahimsa, and how its meaning evolved. Mayrhofer as well as Dumot suggest the root word may be han which means kill, which leads to the interpretation that ahimsa means do not kill. Schmidt as well as Bodewitz explain the proper root word is hiṃs and the Sanskrit verb hinasti, which leads to the interpretation that ahimsa means do not injure, or do not hurt. Wackernagel-Debrunner (and Sarkar) concur with the latter explanation.[9][10]

History

The concept of ahimsa first arose as an ethical precept in the indigenous tantric tradition of ancient India. Over time, the concept of ahimsa made its way into Vedic texts with varying interpretations. When the philosopher wikipedia:Patanjali (circa 200-400BCE) systematized tantra into what is popularly known as Aśt́áuṋga Yoga (eight-limbed yoga) or Rája Yoga (the king of yogas), ahimsa was the first principle of his first element of yoga (Yama).[11]

Jainism

- Main article: Ahimsa in Jainism

In Jainism, the understanding and implementation of Ahimsa is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in any other religion.[12] Non-violence is seen as the most essential religious duty for everyone (ahiṃsā paramo dharmaḥ, a statement often inscribed on Jain temples).[13] Like in Hinduism, the aim is to prevent the accumulation of harmful karma.[14] When Mahavira revived and reorganized the Jain movement in the 6th or 5th century BCE,[15] Ahimsa was already an established, strictly observed rule.[16] Parshva, the earliest Jain Tirthankara, whom modern Western historians consider to be a historical figure,[17] lived in about the 8th century BCE.[18] He founded the community to which Mahavira’s parents belonged.[19] Ahimsa was already part of the "Fourfold Restraint" (Caujjama), the vows taken by Parshva’s followers.[20] In the times of Mahavira and in the following centuries, Jains were at odds with both Buddhists and followers of the Vedic religion or Hindus, whom they accused of negligence and inconsistency in the implementation of Ahimsa.[21] There is some evidence, however, that ancient Jain ascetics accepted meat as alms if the animal had not been specifically killed for them.[22] Modern Jains deny this vehemently, especially with regard to Mahavira himself.[23] According to the Jain tradition either lacto vegetarianism or veganism is mandatory.[24]

The Jain concept of Ahimsa is characterized by several aspects. It does not make any exception for ritual sacrificers and professional warrior-hunters. Killing of animals for food is absolutely ruled out.[25] Jains also make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life as far as possible. Though they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants.[26] Jains go out of their way so as not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals.[27] For example, Jains often do not go out at night, when they are more likely to step upon an insect. In their view, injury caused by carelessness is like injury caused by deliberate action.[28] Eating honey is strictly outlawed, as it would amount to violence against the bees.[29] Some Jains abstain from farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of many small animals, such as worms and insects,[30] but agriculture is not forbidden in general and there are Jain farmers.[31] Additionally, because they consider harsh words to be a form of violence, they often keep a cloth to ritually cover their mouth, as a reminder not to allow violence in their speech.

In contrast, Jains agree with Hindus that violence in self-defense can be justified,[32] and they agree that a soldier who kills enemies in combat is performing a legitimate duty.[33] Jain communities accepted the use of military power for their defense, and there were Jain monarchs, military commanders, and soldiers.[34]

Though, theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, Jains admit that this ideal cannot be completely implemented in practice. Hence, they recognize a hierarchy of life. Mobile beings are given higher protection than immobile ones. For the mobile beings, they distinguish between one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed and five-sensed ones; a one-sensed animal has touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more they care about its protection. Among the five-sensed beings, the rational ones (humans) are most strongly protected by Jain Ahimsa.[35] In the practice of Ahimsa, the requirements are less strict for the lay persons who have undertaken anuvrata (Lesser Vows) than for the monastics who are bound by the Mahavrata "Great Vows".[36]

Buddhism

Unlike in Hindu and Jain sources, in ancient Buddhist texts Ahimsa (or its Pāli cognate avihiṃsā) is not used as a technical term.[37] The traditional Buddhist understanding of non-violence is not as rigid as the Jain one, but like the Jains, Buddhists have always condemned the killing of all living beings.[38][39] In some Buddhist traditions vegetarianism is not mandatory. In these traditions, monks and lay persons may eat meat and fish on condition that the animal was not killed specifically for them.[40] For some monks, specifically monks of some Mahayana traditions, the eating of meat is strictly forbidden. Laypeople are also encouraged to eat vegetarian.

Since the beginnings of the Buddhist community, monks and nuns have had to commit themselves to the Five Precepts of moral conduct.[39] In ancient Buddhism, lay persons were encouraged, but not obliged, to commit themselves to observe the Five Precepts of morality (Pañcasīla).[41] In both codes the first rule is to abstain from taking the life of a sentient being (Pānātipātā).[42] Buddhist monks should avoid cutting or burning trees, because some sentient beings rely on them.[43]

War

Unlike the Vedic religion, ancient Buddhism had strong misgivings about violent ways of punishing criminals and war. Neither was explicitly condemned,[44] but peaceful ways of conflict resolution and punishment with the least amount of injury were encouraged.[45][46] The early texts condemn the mental states that lead to violent behavior.[47]

Non-violence is an over-riding concern of the Pali Canon.[48] While the early texts condemn killing in the strongest terms, and portray the ideal king as a pacifist, such a king is nonetheless flanked by an army.[49] It seems that the Buddha's teaching on non-violence was not interpreted or put into practice in an uncompromisingly pacifist or anti-military-service way by early Buddhists.[49] The early texts assume war to be a fact of life, and well-skilled warriors are viewed as a necessity for defensive warfare.[50] In Pali texts, injunctions to abstain from violence and involvement with military affairs are directed at members of the sangha; later Mahayana texts, which often generalize monastic norms to laity, require this of lay people as well.[51]

The early texts do not contain just-war ideology as such.[52] Some argue that a sutta in the Gamani Samyuttam rules out all military service. In this passage, a soldier asks the Buddha if it is true that, as he has been told, soldiers slain in battle are reborn in a heavenly realm. The Buddha reluctantly replies that if he is killed in battle while his mind is seized with the intention to kill, he will undergo an unpleasant rebirth.[53] In the early texts, a person's mental state at the time of death is generally viewed as having an inordinate impact on the next birth.[54]

Some Buddhists point to other early texts as justifying defensive war.[55] One example is the Kosala Samyutta, in which King Pasenadi, a righteous king favored by the Buddha, learns of an impending attack on his kingdom. He arms himself in defense, and leads his army into battle to protect his kingdom from attack. He lost a battle but won the war. King Pasenadi defeated King Ajatasattu and captured him alive. He thought that although this King of Magadha has transgressed against his kingdom, he had not transgressed against him personally, and Ajatasattu is still his nephew. He released Ajatasattu and did not harm him.[56] Upon his return, the Buddha says, among other things, that Pasenadi is "a friend of virtue, acquainted with virtue, intimate with virtue", while the opposite is said of the aggressor, King Ajatasattu.[57]

According to Theravada commentaries, there are five requisite factors that must all be fulfilled for an act to be both an act of killing and to be karmically negative. These are: (1) the presence of a living being, human or animal; (2) the knowledge that the being is a living being; (3) the intent to kill; (4) the act of killing by some means; and (5) the resulting death.[58] Some Buddhists have argued on this basis that the act of killing is complicated, and its ethicization is predicated upon intent.[59] Some have argued that in defensive postures, for example, the primary intention of a soldier is not to kill, but to save, and the act of killing in that situation would have minimal negative karmic repercussions.[60]

According to Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, the doctrine of Ahimsa does not state "kill not" but rather "love all". Buddha said "Love all, so that you may not wish to kill any." This is a positive way of stating the principle of Ahimsa. The Buddha's Ahimsa is quite in keeping with his middle path. To put it differently, the Buddha made a distinction between a principle and a rule. He did not make Ahimsa a matter of rule. He enunciated it as a matter of principle. A principle leaves you freedom to act; a rule does not.[61]

Laws

The emperors of Sui dynasty, Tang dynasty and early Song dynasty banned killing in Lunar calendar 1st, 5th, and 9th month.[62][63][64] Empress Wu Tse-Tien banned killing for more than half a year in 692.[65] Some also banned fishing for some time each year.[66]

The King Bayinnaung of Burma, after conquering the Bago in 1559, the Buddhist King prohibited the practice of halal, specifically, killing food animals in the name of God. He also disallowed the Eid al-Adha religious sacrifice of cattle. Halal food was also forbidden by king Alaungpaya in the 18th century.

There were bans after death of emperors,[67][68] Buddhist and Taoist prayers, [69][70] Health concerns[71][72][73] and natural disasters such as after a drought in 1926 summer Shanghai[74] and a 8 days ban from August 12, 1959 after the August 7 flood (八七水災), the last big flood before the 88 Taiwan Flood.[75][76] There was a 3-day ban after the death of Chiang Kai-shek.[77]

People avoid killing during some festivals, like the Taoist Ghost Festival,[78] the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, the Vegetarian Festival and many others.[79][80][81][82][83]

References

- ^ Rune E. A. Johansson (6 December 2012) Pali Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader and Grammar Routledge p. 143 ISBN 978-1-136-11106-8 retrieved 8 August 2013

- ^ Mayton, D. M., & Burrows, C. A. (2012), Psychology of Nonviolence, The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, Vol. 1, pages 713-716 and 720-723, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9644-4

- ^ [Encyclopedia Britannica], see Ahimsa

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedevpc - ^ a b Anandamurti, Shrii Shrii (2004) A Guide to Human Conduct ISBN 9788172521035

- ^ a b Sanskrit dictionary reference

- ^ Standing, E. M. (1924). THE SUPER‐VEGETARIANS. New Blackfriars, 5(50), pages 103-108

- ^ A Hindu Primer, by Shukavak N. Dasa

- ^ Henk Bodewitz (in Jan E. M. Houben, Karel Rijk van Kooij, Eds.), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History, ISBN 978-9004113442, Brill Academic Pub (June 1999), see Chapter 2

- ^ Walli pp. XXII-XLVII; Borman, William: Gandhi and Non-Violence, Albany 1986, p. 11-12.

- ^ Patañjali: Yoga Sutras, Sadhana Pada 30.

- ^ Laidlaw, pp. 154–160; Jindal, pp. 74–90; Tähtinen p. 110.

- ^ Dundas, Paul: The Jains, second edition, London 2002, p. 160; Wiley, Kristi L.: Ahimsa and Compassion in Jainism, in: Studies in Jaina History and Culture, ed. Peter Flügel, London 2006, p. 438; Laidlaw pp. 153–154.

- ^ Laidlaw pp. 26–30, 191–195.

- ^ Dundas p. 24 suggests the 5th century; the traditional dating of Mahavira’s death is 527 BCE.

- ^ Goyal, S.R.: A History of Indian Buddhism, Meerut 1987, p. 83-85.

- ^ Dundas pp. 19, 30; Tähtinen p. 132.

- ^ Dundas p. 30 suggests the 8th or 7th century; the traditional chronology places him in the late 9th or early 8th century.

- ^ Acaranga Sutra 2.15.

- ^ Sthananga Sutra 266; Tähtinen p. 132; Goyal p. 83-84, 103.

- ^ Dundas pp. 160, 234, 241; Wiley p. 448; Granoff, Phyllis: The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices, in: Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 15 (1992) pp. 1–43; Tähtinen pp. 8–9.

- ^ Alsdorf pp. 564–570; Dundas p. 177.

- ^ Alsdorf pp. 568–569.

- ^ Laidlaw p. 169.

- ^ Laidlaw pp. 166–167; Tähtinen p. 37.

- ^ Lodha, R.M.: Conservation of Vegetation and Jain Philosophy, in: Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment, New Delhi 1990, p. 137-141; Tähtinen p. 105.

- ^ Jindal p. 89; Laidlaw pp. 54, 154–155, 180.

- ^ Sutrakrtangasutram 1.8.3; Uttaradhyayanasutra 10; Tattvarthasutra 7.8; Dundas pp. 161–162.

- ^ Hemacandra: Yogashastra 3.37; Laidlaw pp. 166–167.

- ^ Laidlaw p. 180.

- ^ Sangave, Vilas Adinath: Jaina Community. A Social Survey, second edition, Bombay 1980, p. 259; Dundas p. 191.

- ^ Nisithabhasya (in Nisithasutra) 289; Jinadatta Suri: Upadesharasayana 26; Dundas pp. 162–163; Tähtinen p. 31.

- ^ Jindal pp. 89–90; Laidlaw pp. 154–155; Jaini, Padmanabh S.: Ahimsa and "Just War" in Jainism, in: Ahimsa, Anekanta and Jainism, ed. Tara Sethia, New Delhi 2004, p. 52-60; Tähtinen p. 31.

- ^ Harisena, Brhatkathakosa 124 (10th century); Jindal pp. 90–91; Sangave p. 259.

- ^ Jindal pp. 89, 125–133 (detailed exposition of the classification system); Tähtinen pp. 17, 113.

- ^ Dundas pp. 158–159, 189–192; Laidlaw pp. 173–175, 179; Religious Vegetarianism, ed. Kerry S. Walters and Lisa Portmess, Albany 2001, p. 43-46 (translation of the First Great Vow).

- ^ Tähtinen p. 10.

- ^ Sarao, p. 49; Goyal p. 143; Tähtinen p. 37.

- ^ a b Lamotte, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Sarao pp. 51–52; Alsdorf pp. 561–564.

- ^ Lamotte pp. 69–70.

- ^ Lamotte p. 70.

- ^ 從律典探索佛教對動物的態度(中). Awker.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ Sarao p. 53; Tähtinen pp. 95, 102.

- ^ Tähtinen pp. 95, 102–103.

- ^ Kurt A. Raaflaub, War and Peace in the Ancient World. Blackwell Publishing, 2007 , p. 61.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, p. 52.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, p. 111.

- ^ a b Bartholomeusz, p. 41.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, p. 50.

- ^ Stewart McFarlane in Peter Harvey, ed., Buddhism. Continuum, 2001, pages 195–196.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, p. 40.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, pp. 125–126. Full texts of the sutta:[1].

- ^ Rune E.A. Johansson, The Dynamic Psychology of Early Buddhism. Curzon Press 1979, page 33.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, pp. 40–53. Some examples are the Cakkavati Sihanada Sutta, the Kosala Samyutta, the Ratthapala Sutta, and the Sinha Sutta. See also page 125. See also Trevor Ling, Buddhism, Imperialism, and War. George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1979, pages 136–137.

- ^ Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-331-1.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, pp. 49, 52–53.

- ^ Hammalawa Saddhatissa, Buddhist Ethics. Wisdom Publications, 1997, pages 60, 159, see also Bartholomeusz page 121.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, p. 121.

- ^ Bartholomeusz, pp. 44, 121–122, 124.

- ^ The Buddha and His Dhamma. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 卷糺 佛教的慈悲觀. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 試探《護生畫集》的護生觀 高明芳

- ^ 唐《開元二十五年令•雜令》研究. Flwh.znufe.edu.cn (2007-02-28). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 「護生」精神的實踐舉隅. Ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 答妙贞十问. Cclw.net. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 第一二八期 佛法自由談. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 贵阳南明-生态文明城区. Gz.xinhuanet.com (2007-07-06). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 虛雲和尚法彙—書問. Bfnn.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 五朝祈安清醮三重全市茹素三天祈福. Epochtimes.com (2010-11-18). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 比利时出现口蹄疫欧陆如临大敌. News.dayoo.com (2001-03-04). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 吉林启动禽流感应急预案 长春活禽市场全关闭. 022net.com (2005-11-05). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 阆中古城首接“禁屠令”. Morning.scol.com.cn (2004-08-24). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 灾异. shtong.gov.cn

- ^ 組員:余秉育[dead link]

- ^ 道安長老年譜. Plela.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 陈立夫[dead link]

- ^ 农历中元节. Sx.chinanews.com.cn. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 明溪县“禁屠日”习俗的由来

- ^ 滇西独特的禁屠护兽节. Godpp.gov.cn (2006-01-09). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ "「四月六、七、八日禁屠三天」的玄機!!" archived from the original on 2009-10-24

- ^ 建构的节日:政策过程视角下的唐玄宗诞节. Chinesefolklore.org.cn (2008-02-16). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- ^ 我国古代生态保护资料的新发现. Economy.guoxue.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

Bibliography

- Alsdorf, Ludwig (1962) Beiträge zur Geschichte von Vegetarismus und Rinderverehrung in Indien Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur; in Kommission bei F. Steiner Wiesbaden retrieved 15 June 2011

- Bartholomeusz, Tessa In Defense of Dharma. RoutledgeCurzon 2002 ISBN 0-7007-1681-5

- Jindal, K.B.: An epitome of Jainism, New Delhi 1988 ISBN 81-215-0058-3

- Laidlaw, James: Riches and Renunciation. Religion, economy, and society among the Jains, Oxford 1995 ISBN 0-19-828031-9

- Lamotte, Etienne: History of Indian Buddhism from the Origins to the Śaka Era, Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 ISBN 90-6831-100-X

- Sarao, K.T.S.: The Origin and Nature of Ancient Indian Buddhism, Delhi 1989

- Schmidt, Hanns Peter: The Origin of Ahimsa, in: Mélanges d'Indianisme à la mémoire de Louis Renou, Paris 1968

- Tähtinen, Unto: Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London 1976 ISBN 0-09-123340-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ahimsa. |

- Ahimsa quotations from Puranic scripture (vedabase.net)

- Gandhi, Hinduism and Non-Violence at the United Nations by Varun Soni

- REDIRECT Template:Indian philosophy

- Pages with reference errors

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from June 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles containing non-English-language text

- Pages with broken file links

- Commons category with local link different than on Wikidata

- Buddhist philosophical concepts

- Ethical schools and movements

- Hindu philosophical concepts

- Jain philosophical concepts

- Pacifism