Ahimsa

| Ahimsa | |

|---|---|

| In other languages |

Non-violence (English) अहिंसा (Sanskrit) |

| Location in Sarkarverse | |

Ahimsa (Sanskrit: अहिंसा; Roman Saḿskrta: ahiḿsá; IAST: ahiṃsā, Pali:[1] avihiḿsá) is a term meaning benignity, non-injury. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root hiḿs – to strike. Hiḿsá is injury or harm. A-hiḿsá is the opposite.[2][3]

Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues[4], the first of ten principles in the ancient tantric/yogic system of morality, Yama-Niyama. As such, it is also an important tenet of major Indian religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism). Over the years, Ahimsa has been interpreted in many different ways. In his book, A Guide to Human Conduct, Sarkar analyzes the concept of Ahimsa and some popular interpretations of the term.[5]

Etymology

The word Ahimsa - sometimes spelled as Ahinsa[6][7] - is derived from the Sanskrit root hiṃs – to strike; hiṃsā (or hiḿsá in Sarkar's Roman Sanskrit) is injury or harm, a-hiṃsā is the opposite of this, that is benignity or non-jury.[6][8] According to Sarkar, "Ahiḿsá means not inflicting pain or hurt on anybody by thought, word or action."[5]

There is a debate on the origins of the word Ahimsa, and how its meaning evolved. Mayrhofer as well as Dumot suggest the root word may be han which means kill, which leads to the interpretation that ahimsa means do not kill. Schmidt as well as Bodewitz explain the proper root word is hiṃs and the Sanskrit verb hinasti, which leads to the interpretation that ahimsa means do not injure, or do not hurt. Wackernagel-Debrunner (and Sarkar) concur with the latter explanation.[9][10]

History

| Yama (Restraint) | |

|---|---|

| Ahiḿsá (Benignity) | Thinking, speaking, and acting without inflicting pain or harm on another |

| Satya (Benevolence) | Thinking and speaking with goodwill |

| Asteya (Honesty) | Not taking or keeping what belongs to others |

| Brahmacarya (Ideation) | Constant mental association with the Supreme |

| Aparigraha (Frugality) | Non-indulgence in superfluous amenities |

| Niyama (Regulation) | |

| Shaoca (Cleanliness) | Physical and mental purity, both internal and external |

| Santośa (Contentment) | Maintaining a state of mental ease |

| Tapah (Sacrifice) | Acceptance of sufferings to reach the spiritual goal |

| Svádhyáya (Contemplation) | Clear understanding of any spiritual subject |

| Iishvara Prańidhána (Dedication) | Adopting the Cosmic Controller as the only ideal of life and moving with ever-accelerating speed toward that Desideratum |

| Intent is primary, but both intent and action should conform if possible. | |

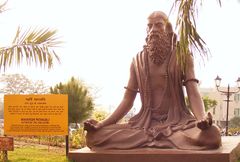

The concept of ahimsa first arose as an ethical precept in the indigenous tantric tradition of ancient India. Over time, the concept of ahimsa made its way into Vedic texts with varying interpretations. When the philosopher Patanjali (circa 200-400BCE) systematized tantra into what is popularly known as Aśt́áuṋga Yoga (eight-limbed yoga) or Rája Yoga (the king of yogas), ahimsa was the first principle of his first element of yoga, Yama.[11]

Various interpretations of Ahimsa

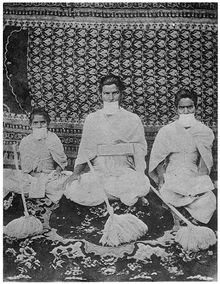

In both Jainism and Buddhism, both circa 500BCE, ahimsa is a key ethical principle. In Jainism, it is the first and main ethical principle. Jain renunciates reject the use of force even when it is required for self-defense. They are often seen wearing a mask over their mouth to avoid the unintentional ingestion of flies. And they have also been known to pour sugar into anthills.[5] Buddhists observe a somewhat less strict interpretation of ahimsa. For example, unlike Jains, not all Buddhists are vegetarian.

In modern times, the concept of ahimsa has taken on a new meaning, in large part due to the teachings and activities of Mohandas Gandhi. According to Gandhi, ahimsa means non-violence. This is perhaps the most extreme interpretation of ahimsa, given the fact that even Jains and Hindus accept the use of violence in self-defense.[12][13]

Sarkar on ahimsa

According to Sarkar, principles of morality must take into account both action and intent. When there is an unavoidable conflict between the two, intent becomes primary. So Sarkar notes with respect to ahimsa that violence (or the use of force) is both natural and unavoidable. Hence, ahimsa cannot be reasonably interpreted to mean the non-use of force.[5]

Life feeds on life. So, for example, our choice is to drink purified or unpurified water. In both instances, we end up killing microbes, either outside or inside our body. Hence, with respect to food, Sarkar endorsed a gradation rule, similar to that of the Jains, whereby food is selected with an effort to maintain a healthy body and mind by taking sustenance from entities with the least self-awareness. When it is possible to remain healthy by subsisting on grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, nuts and the like, then there is no justification for killing animals or even fish to eat their flesh.[5]

According to Sarkar, morality does not suppress the natural instinct for survival. So, with respect to self-defense, Sarkar argues that combat against an aggressor (átatáyii in Samskrta) is not just acceptable but even noble. Sarkar notes that Krsna encouraged the Pandavas to do battle with the Kaoravas, because they were aggressors.[5]

References

- ^ Rune E. A. Johansson (6 December 2012) Pali Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader and Grammar Routledge p. 143 ISBN 978-1-136-11106-8 retrieved 8 August 2013

- ^ Mayton, D. M., & Burrows, C. A. (2012), Psychology of Nonviolence, The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, Vol. 1, pages 713-716 and 720-723, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9644-4

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, see Ahimsa

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips & other authors (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (Second Edition), ISBN 978-0123739858, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701-849, 1867

- ^ a b c d e f Anandamurti, Shrii Shrii (2004) A Guide to Human Conduct ISBN 9788172521035

- ^ a b Sanskrit dictionary reference

- ^ Standing, E. M. (1924). THE SUPER‐VEGETARIANS. New Blackfriars, 5(50), pages 103-108

- ^ A Hindu Primer, by Shukavak N. Dasa

- ^ Henk Bodewitz (in Jan E. M. Houben, Karel Rijk van Kooij, Eds.), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History, ISBN 978-9004113442, Brill Academic Pub (June 1999), see Chapter 2

- ^ Walli pp. XXII-XLVII; Borman, William: Gandhi and Non-Violence, Albany 1986, p. 11-12.

- ^ Patañjali: Yoga Sutras, Sadhana Pada 30.

- ^ Nisithabhasya (in Nisithasutra) 289; Jinadatta Suri: Upadesharasayana 26; Dundas pp. 162–163; Tähtinen p. 31.

- ^ Jindal pp. 89–90; Laidlaw pp. 154–155; Jaini, Padmanabh S.: Ahimsa and "Just War" in Jainism, in: Ahimsa, Anekanta and Jainism, ed. Tara Sethia, New Delhi 2004, p. 52-60; Tähtinen p. 31.